Day 4

Today was our first full day at the hospital, although “full” is an understatement. When we opened the clinic at 10am, the open-air waiting room was teeming with patients and their families lining rows of benches or sprawled on mats on the floor.

The team got right to work; Sherry and Rob left to set up our supply room and prepare equipment for surgery the next day. Izzy, Zvi, Danielle and I were joined by the hospital’s own orthopedic surgeon, Dr. Deo. We parked ourselves in a small room with an examining table and brought in the first patient. Over the next ten and a half hours, we screened 67 patients and selected 16 as candidates for surgery pending results from their imaging. It was a long day, and at times a bit trying; after hours of sitting on a bench in a dark, hot, narrow hallway with minimal food and water, patients began pushing their way into the small examining room. They were understandably anxious; many of them had travelled long distances to Mbarara just to be seen by Dr. Lieberman. We explained sympathetically that we were moving as fast as we could, and they would simply have to wait longer. I was astonished by their patience and resilience. Amina, a thin, frail 85-year old woman with chronic back pain from spinal stenosis shuffled slowly into the examining room with a walking stick. The deep wrinkles in her face folded into themselves each time she winced, emphasizing the extent of her pain. For over 5 hours she had waited quietly and without complaint. After his examination, Dr. Lieberman explained to Amina that he could treat her pain through a surgical procedure called a decompression, though the surgery would carry significant risk given her age. This brave elderly woman became our first surgical patient the following morning.

As the day dragged on we began to appreciate a specific luxury of North American medical care: the process of waiting. To Canadians like myself and Zvi, waiting a month to see a specialist elicits a groan and some exasperated comment about “the drawbacks of universal healthcare.” Waiting over an hour in an air-conditioned waiting room with cushioned seats and a Starbucks in the lobby prompts a similar reaction. Many of these Ugandan patients had lived for over 20 years with back pain. We saw teenagers and 20-somethings with spine deformities that in North America would have been corrected within the first two decades of their lives. Here, “waiting” is measured in years rather than weeks or months.

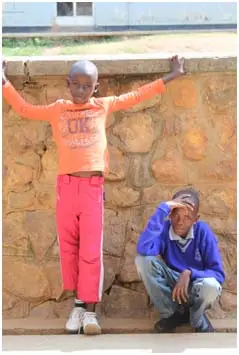

For some patients, their long-awaited visit with Dr. Lieberman brought bittersweet news: they were candidates for surgery, but would have to wait even longer. Kenneth, a short 18-year old with a pockmarked face and a big smile, was born with severe scoliosis and has developed restrictive lung disease as a result of his rigid spine. He walks stooped over to the right because his scoliosis forces his left shoulder upwards. Unable to work with his deformity, Kenneth was hoping that an operation would restore his physical mobility and give him “purpose,” as he put it. But to treat Kenneth’s condition the spine surgery team would need three weeks in Uganda, and we only have six operating days here. Dr. Lieberman explained to Kenneth that he would have to wait until next year when there is the possibility of a longer mission.

67 patients later, we were done for the day. On the drive back to the hotel, we reflected on some of the cases from that day, including Bernadette, a 45 year-old woman who injured her back while pulling a goat tethered to her waist. When one team member wondered aloud why anyone would tie themselves to a goat, Rob kindly provided an answer, as well as our quote of the day: “If you haven’t mutton-busted, you haven’t lived.”

Day 5

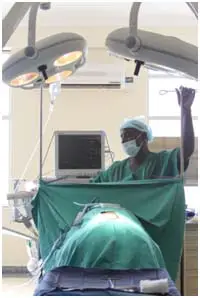

A lot was riding on today: our first day in the OR, our chance to test out the facilities and to work alongside new Ugandan colleagues. Today’s successes and failures would mold our expectations of what we can accomplish in a week and would give us a sense of the challenges we would face. For that reason, Dr. Lieberman deliberately selected a relatively straightforward procedure for our first operation, a posterior decompression in which portions of bone are removed to allow more space around a nerve root. We arrived at the hospital around 8:30am and went straight to the operating room to find the anesthesiologist, Dr. Emanuel already prepping the patient, Amina.

Sherri and Rob snapped into action and began setting up instrument tables and equipment while Izzy and Zvi scrubbed in. It seemed like we were off to a good start….. until the power shut off. We stood in the window-lit operating room with the patient on the ventilator for about 20 minutes until power returned. The rest of the operation went smoothly and two hours later Amina was on her way to the ICU.

With a lunchtime clinic scheduled in between surgeries, we barely had time to scarf down our energy bars before heading out to the corridor of waiting patients. One by one, the patients approached Izzy and Zvi holding their X-rays and CT scans. We were able to add two patients to our list of surgical candidates, and sent several more for imaging and follow-up.

In the meantime, Sherri began setting up the OR for the next case, 56 year-old Muhamoud. Muhamoud had severe vertebral lysis caused by tuberculosis in his spine. I was particularly excited for this case because Dr. Lieberman was planning to approach the spine anteriorly (from the patient’s front), navigating around the peritoneum (the space behind the abdominal organs) to the vertebral column. As Dr. Lieberman went to make his incision, he looked up to find that the anesthesiologist had left the room, leaving his nurse anaesthetist in the pilot’s seat. This wasn’t the only hiccup we would encounter that afternoon. As Dr. Lieberman pulled back the iliac vein to find the vertebral column, the nurse anaesthetist tumbled from his chair, grabbed at the ventilator tubing and crashed into the operating room table causing the patient to move. It was simply luck that the vein between Dr. Lieberman’s forceps did not tear.

That night at dinner, the team discussed some of the lessons of the day. Our first two surgeries in new territory were sobering examples of the importance of thinking on your feet. When things don’t go as planned, improvise. Today’s challenges also highlighted some of the prerequisites of good teamwork. Teams of longstanding colleagues (like the Texas team) work like well-oiled machines. They anticipate each other’s moves, communicate effectively, share expectations and have standard procedures that help things move smoothly. When veteran teams join forces with new colleagues (as the Texas team did with the Ugandan anesthesia team), processes that used to be fluid can suddenly become turbulent. Care must be taken to communicate effectively, lay down expectations and establish roles and responsibilities. Perhaps today’s anesthetic troubles were not from a lack of competence, but rather from miscommunication and incongruent standard practices.

Finally, and on a more personal level, I learned today that surgery is far more multidimensional than I had thought. Spine surgeries don’t necessarily need to be approached from the back, just like heart surgeries aren’t always approached from the anterior chest. Each approach involves different anatomy and with that, different challenges, considerations and risks. The human body is sort of like a labyrinth for the surgeon; sometimes, the best way of reaching a point of interest is not necessarily the most direct route.

All in all, our first surgical day was a great success. As a team, we fell naturally into our own roles and got through our first two surgeries with only a couple nicks along the way. It seemed like we could count on a very productive and rewarding week ahead.