Day 8

Today’s first surgical patient doesn’t have a first name. At least, as far as his medical records at Mbarara are concerned, his first name is C. C is a sixty-five year-old man who is, for all intents and purposes, a wheelchair-bound quadriplegic. Degenerative changes in his cervical spine (his neck) have compressed and damaged the spinal cord, leaving him with paralysis in his legs, a loss of bowel and bladder function, minimal function in his right hand and none in his left that has progressed over three months. Given this clinical picture, I was certainly caught off guard when, while lying flaccid on the operating table awaiting his anesthetic, C asked me whether the operation would allow him to walk again. I passed the question on to Dr. Lieberman anticipating an apologetic response and was astonished to hear that indeed, Dr. Lieberman hoped the operation would accomplish just that.

Similar to Prudence’s operation, Dr. Lieberman approached C’s vertebral column through the side of his neck, navigating around some critical anatomy. He handed me a retractor he was using to push aside a vessel and asked, “What are you holding right now?” “The common carotid,” I replied, referring to the main artery carrying blood to the head. “Correct,” he said, “if you slip, the patient will have a stroke.” Needless to say my hand cramped up a bit while standing there. Unlike most of the operations so far, C’s progressed without any surprises from our hosts (finally, no power outages!) and before we knew it, his decompression (making more room for the spinal cord) and reconstruction (rebuilding and fusing the bones together) was complete. We were very soon ready for our second patient Ida, who was being walked (yes, walked!) into the OR for her surgery that afternoon.

Ida chose to walk (with some help) to the operating room prior to her surgery

Ida chose to walk (with some help) to the operating room prior to her surgery

Ida was not a new patient. Dr. Lieberman had operated on her cervical spine (the part in her neck) last year. She now returned with pain, weakness and tingling in her legs caused by spinal stenosis (when the spinal canal is narrowed and compresses the nerves in the cord). Last week, Ida had walked into our clinic slowly and with an unsteady gait, supported by her son who has since not left her side at the hospital for more than 20 minutes to stretch his legs. She wore a kind expression on her face that day that, along with her son’s iconic NY Yankees baseball cap, have made lasting impressions on us. Now, as Ida was assisted onto the surgical bed, I thought about her son who was undoubtedly pacing outside the double doors to the surgical wing, sporting his distinctive cap.

During Ida’s surgery, Dr. Lieberman carved out space around the compressed portions of the spinal cord and secured screws and rods in place to stabilize the spine. The highlight of my week came next, when Dr. Lieberman allowed me to secure a few screws and to help suture the incision. It’s a small thing for a surgeon, but as a medical student it was the first time I would leave my physical mark on a patient. The fact that it was kind-faced Ida who would carry the scars of those stitch marks made it even more meaningful.

Ida, her son and niece in the private ward the day after her surgery

Ida, her son and niece in the private ward the day after her surgery

The following day, I went to visit Ida and her son in the private surgical wards. Aside from a bit of pain, she was in great shape. As her son walked me out to the corridor, we chatted about their experience throughout his mother’s care. They had tolerated the crowded mini bus system over the 300 kilometer trip from Kampala to see us in Mbarara, only to find themselves completely disoriented and without instruction upon arrival at the hospital. Once admitted (to the private ward, no less), they had to provide their own food, bathing basin and other essentials. There were showers for those in the private ward, but no accommodations for a bed-ridden spine surgery patient. After speaking with Ida’s son, it was clear to me that in Mbarara and perhaps Uganda at large, a patient must be his or her own advocate. Without a middle man to coordinate between patient and doctor, the patient’s own initiative determines the outcome of his or her care. In fact, when it was time for Ida’s surgery, no nurse came to retrieve her. Exasperated, her son walked his mother to the surgical ward and received her stretcher after the operation was complete. The lesson of the day was embedded here: As part of the surgical team, I had a narrow view of our patient’s experience; as far as I knew, she had showed up to our clinic, arrived at the hospital for admission several days prior to surgery, and had made her way to the operating table just as was meant to be. But in between those encounters, Ida and her son had fought to get attention from uninterested nurses and administrators and had navigated a non-intuitive system in their efforts to seek optimal health care.

Day 9

After a surprisingly smooth day yesterday, we had a few curveballs thrown our way today (lest we should get too spoiled with things going as planned!) Our first patient today was Catherine, a 14 year-old girl with a large thoracic kyphosis (an over-pronounced curve in her upper back). Catherine’s condition was consistent with Scheurmann’s disease, a pathology of abnormal bone growth causing wedge-shaped vertebra that exaggerate the normal thoracic kyphosis. With her deformity, Catherine found it painful to carry baskets of food on her head as is common practice here. Dr. Lieberman’s plan was to straighten Catherine’s curve with metal rods anchored to the spine with vertebral screws. There were several power outages throughout the surgery, during which Dr. Lieberman could not use his ultrasonic bone cutter. Nevertheless, he adapted the procedure to the tools that he had until power returned. He would not be derailed by a simple power loss!

Catherine

Catherine

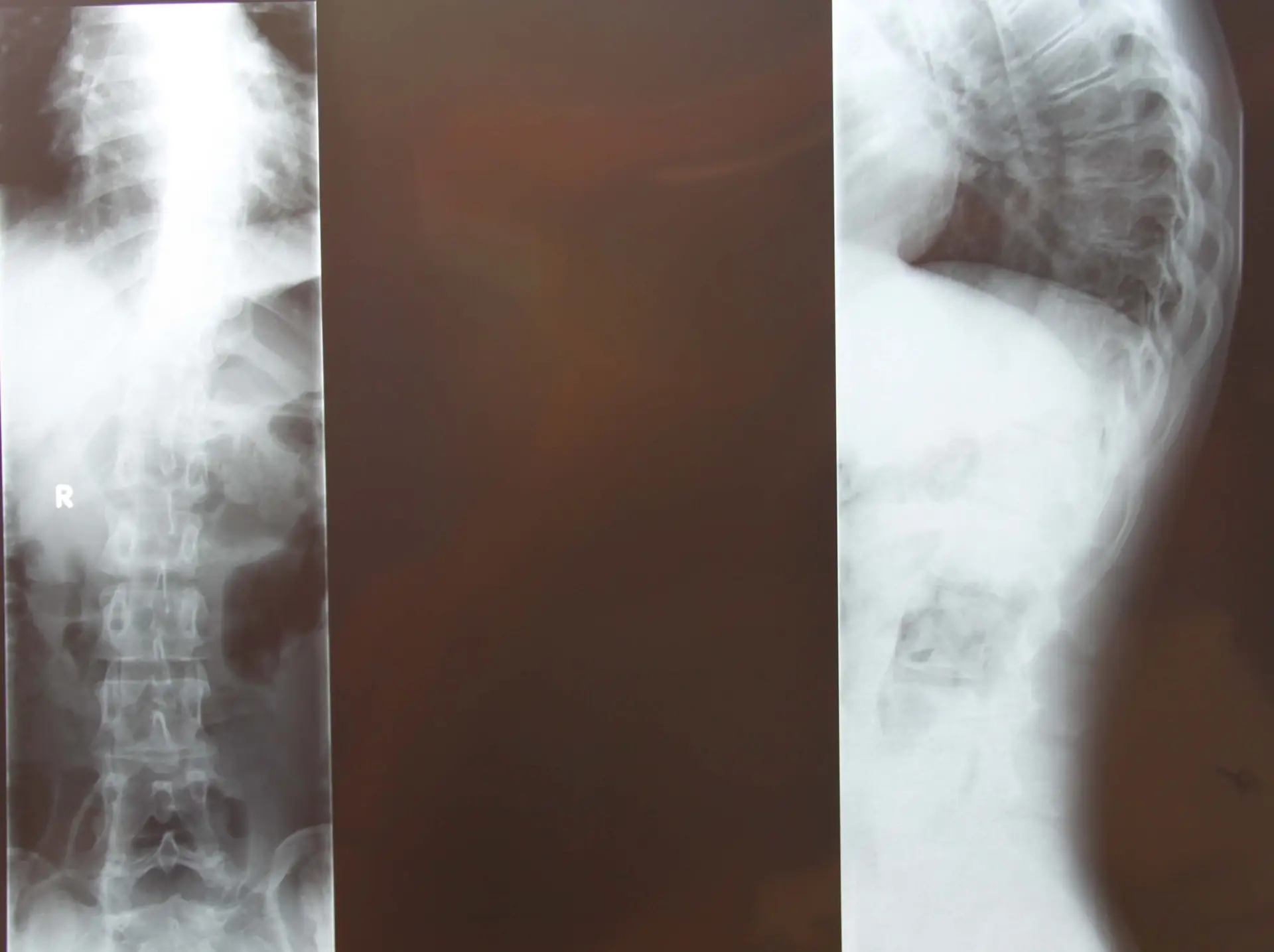

Catherine’s x-rays

Catherine’s x-rays

Our determination to get through the day unscathed met another challenge that afternoon. The autoclave (the machine that sterilizes our equipment between surgeries) failed during its cycle, leaving us potentially still contaminated equipment for the operation. Our second patient, Aguma, who had two level spinal stenosis (narrowing of the spinal canal with compression of the nerves) lay prepped and sleeping on the operating table while Dr. Lieberman, Rob and Sherri brainstormed alternatives. They decided to rerun the sterilization (a 45-minute cycle) while in the meantime proceeding with the operation using alternative tools. Rob scoured the hospital’s sterilized equipment room for substitutes while Sherri went through some of our own tool sets set aside for other procedures. With some creative ingenuity the decompression surgery (laminotomies and foraminotomies) got underway, and 60 minutes into the operation we received our freshly-sterilized equipment.

That evening, the hospital and university invited us to a buffet dinner at the Agip Motel. Those in attendance included the surgical team from the hospital, the university and hospital accountants, and two of the vice deans from the Faculty of Medicine. After the meal, each of our hosts in turn spoke of their gratitude to Dr. Lieberman and his team. They expressed their hope that the continued presence of the mission would allow them to build competence and expertise in spine surgeries, ultimately establishing Mbarara as the pinnacle spine surgery center of East Africa. After a week of hard work in the operating room, the team was moved to see the appreciation and long-term vision of our host institution. After all, we weren’t simply there to operate on ten patients and call it a week. The mission was established to provide spine care to the less fortunate and train those who serve these patients. As the saying goes, “Give a man a fish and he will eat for a day. Teach a man to fish and he will eat for a lifetime.”

dinner with hospital and university faculty and staff

After dinner, the team gathered in our hotel lobby and discussed the lessons of the day over a bottle of wine. Today taught us that surgery can be seen as a series of small failures that simply require some creativity and perseverance to overcome. Back home in the US and Canada, the autoclave failure would have resulted in a canceled/delayed surgery. But here in Uganda, with limited time and even more limited resources, we could not afford to delay the operation. Dr. Lieberman, Rob and Sherri went back to basics in the absence of their standard operating procedures, highlighting the importance of fundamentals in medicine. We saw the challenges of the day—the power outages and the autoclave failure—as tests of what a co-ordinated and experienced surgical team could accomplish when forced to improvise.